Why does Piggydb make your note-taking stand out from the crowd?

Posted: March 16, 2013 Filed under: essay 2 CommentsPiggydb changes the way of note-taking.

Note-taking was originally a top-down process. The ancient people started note-taking to record things on important subjects, using it as a device of artificial memory. Naturally, they needed to organize the contents of the memory well enough to be able to use the accumulated knowledge efficiently. But, because of the physical limitations of the old mediums (stone, wood, etc), they had to decide the structure of content in advance. It leads to so-called linear note-taking.

Linear note-taking is a technique where you take notes sequentially in an outline format (tree structure). In physical mediums, such as paper, you have to make an outline (roughly at least) before taking notes in detail since it is difficult to change the outline structure later. So if you want to create a large document, you need to combine linear and non-linear note-taking (free mapping), and evolve the document by rewriting the whole thing iteratively.

As the personal computing era began, there was a huge breakthrough in this area: the emergence of note-taking software. Note-taking software made restructuring notes extremely easy and allowed users to grow a structure by trial and error with virtually no cost.

This kind of note-taking software is typically called an ‘outliner’. Its more visual and free-formed alternative – mind mapping, has also grown popular among note-taking techniques. The common feature of these techniques is that they let you to take tree-structured notes in a top-down manner.

Let’s look at how this “tree and top-down” note-taking technique looks like in Piggydb.

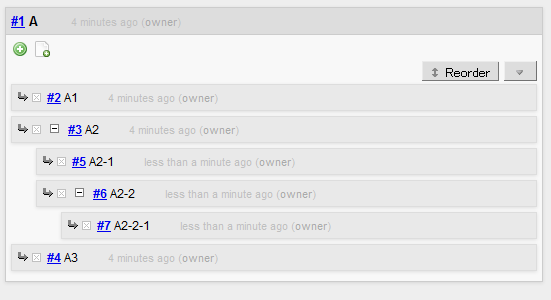

To begin with, you have to select a main topic (A), which becomes the root of the tree you are about to grow. And then, collect subtopics (A1, A2, A3, …) belonging to the main topic:

As you are taking notes, you can add a subtopic to any level of topic to extend the hierarchy:

And later on, you can change the order of any subtopics:

While this “tree and top-down” still seems to be the mainstream of note-taking and other information management techniques, a new trend has emerged in recent years as the amount of information each individual has to deal with increased.

In a tree structure, everything should be well sorted and organized, otherwise you could not find the information you need and when you need it. However, in reality, as the amount and variety of information grows, it becomes more and more difficult to maintain the consistency of the structure and you would end up not organizing it anymore.

As you all know, the technology that has totally changed the situation was search engines. With an effective search engine, you can access the needed piece of information whenever you want as long as you put the whole data into a place where the search engine can access it. This has changed personal information management to a large extent. I believe many of you stopped sorting your emails out when Gmail was introduced, and more generally, manage your information in a personal database such as Evernote.

These technologies have been gradually changing the role of “tree and top-down” so that it is utilized in more limited cases. For example, as a routine, people save incoming daily information to their personal database without sorting it out, and when they want to consider or investigate a certain topic, they search their database for related pieces of information which will become the ingredients of outcome cooked with “tree and top-down” or non-linear note-taking techniques.

It is a quite modern information management and seems to be enough for us to survive in today’s information-oriented world.

However, there is one important area, especially important in today’s world becoming flatter and flatter as a labor market, that these note-taking techniques have not focused on so far.

That is human creativity.

What the traditional note-taking has focused on is, as I mentioned above, extending human memory and efficiently grasping the outline of existing knowledge. But the most important (and interesting) part of intellectual production activities would be the process of discovering unknown concepts from a vast sea of information, not following existing knowledge (yes, it’s still important though).

It is an attempt to restructure the existing system of knowledge.

For most of students who keenly need note-taking, it might be all they could do to follow and absorb existing knowledge. But in order to stand out from the crowd in this digital era where you can get needed information quite easily, you need a technique leading you to the discovery of innovative ideas. That is the bottom-up note-taking Piggydb has proposed.

In bottom-up note-taking, you don’t need to select a main topic. Yet it is quite normal to select a certain topic as a starting point, but you are not bound to be within that area.

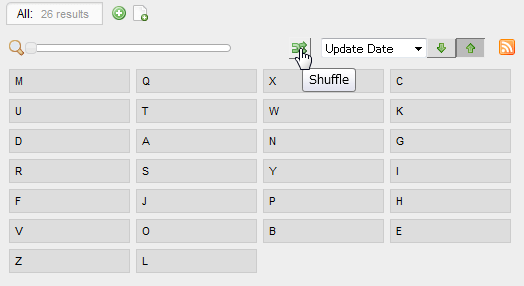

You just put incoming pieces of information into your database one by one:

At the beginning, no remarkable structures are visible. But as the number of the fragments grow and you repeatedly review and shuffle them in the various views,

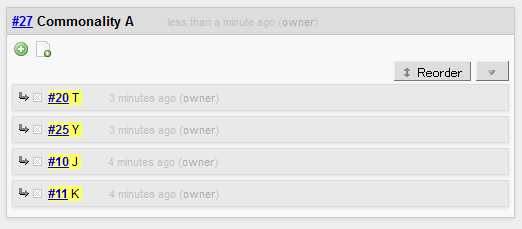

you discover an unexpected commonality across several fragments and create a new fragment representing the commonality:

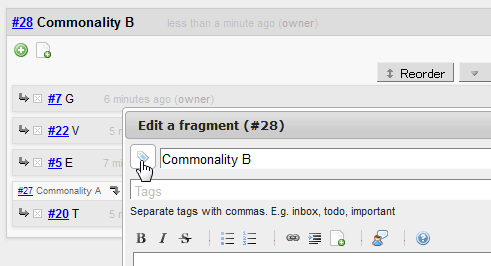

Then, after commonality fragments accumulate to some extent, you pick one that feels important to you and turn it into a tag,

which distinguishes the fragment from others as a concept and provides you with a more useful base to build knowledge of the newborn concept.

That’s a brief introduction to the bottom-up note-taking in Piggydb.

With only “tree and top-down” and a remember-everything-type-of-database, it would not be easy for you to doubt the structure/premises behind the topic you have selected in the first place. These techniques would be good enough to grasp the structure of the cave you are exploring, but not suitable for searching for hidden treasures.

If you are practicing bottom-up note-taking, everyday will be filled with new discoveries. You will arrive at an unexpected destination (in a good sense, of course) and acquire your own thought framework.

Anyway, the best way to understand it is to try it out and experiment yourself. Piggydb is extremely easy to get started, so download the latest version from here and start your journey of knowledge creation right away.

The Piggydb Way: #2 Tags as First-Class Components

Posted: October 20, 2012 Filed under: essay, thepiggydbway 2 CommentsMost of you who happen to stumble upon piggydb.net are sure to know what you want, I imagine. You are looking for a tool (in the categories like wiki, outliner, personal database, etc) that helps you organize your information in a more effective way as an alternative to, for example, Evernote or Springpad. Then suddenly, I began to talk about the ‘reversal process’ instead of explaining the basic organizing functionality. You might be confused or think you didn’t need it because you knew what kind of information you were going to organize and how to organize it, and you just needed a tool to support it. Well, okay, but is that really the case? Are you really sure you know what you want?

When you are about to collect information and organize it, quite naturally, you know what kind of information you are going to organize, and anticipate the result. It may be information about your project, daily routines, a travel plan, or it may be a diary. You have already prepared the container in which you are going to just place pieces of information one by one. It would be quite straightforward, you think. However, once you begin it, something in you will be stimulated by what you are doing, and sooner or later, you will unconsciously step into the area of Knowledge Creation even with a most primitive container you use, such as a piece of paper.

Let’s suppose that you keep a record of things you have done in your daily life in a plain old paper notebook. You do so because you want to use these information later on when you need to know what you did and when you did it. And then, one day, after a while since it became a daily routine, you reflect on the record. In that reflection, you happen to find an interesting pattern in the log. You underline these places with a red pen and write an explanation of the concept common to them in your own way. This discovery is totally what you didn’t expect when you started this habit. I’m sure many of you have experienced something like this before if you have a note-taking habit. Let’s call this kind of practice ‘Weighting Information‘ (selecting a certain part of information and putting some meaning into it). So you acquired a new point of view as a result of weighting information.

Information weighting appears whenever you deal with information. For example, if you are reading this article on a web browser (I believe most of you are), it must have a bookmarking function. Bookmark allows you to save addresses of websites that you want to revisit later, and it can be regarded as a way of information weighting. You select a small bit of the vast sea of the Web and attach the concept of ‘bookmark’ to it.

As you may have noticed in the example of recording things done, there are two steps in information weighting. The first one is the discovery of an interesting commonality across random things and the second one is putting a label on it. In this process, the mechanism of the discovery is especially interesting and mysterious. One of the most interesting things about it is that you can’t expect the outcome in advance, in other words, you can’t plan what kind of thing you are going to discover.

The other day, I came across an interesting column on innovation titled “The Idea Idea” by Peter J. Denning (http://cs.gmu.edu/cne/pjd/PUBS/CACMcols/cacmMar12.pdf). Denning brought skepticism to the popular belief that an innovation is the result of adopting a good idea. He proposed a hypothesis that “practices rather than ideas are the main source of innovation” and “many ideas are therefore afterthoughts to explain innovations that have already happened“. The term ‘idea‘ here can be replaced by ‘concept‘ that we are discussing about. In the above example of information weighting, the concept discovery was not expected or planned but happened in the course of the practice of recording things done in daily life.

Stephen King, a world-renowned novelist, once wrote about his style of writing novels. He wrote in his memoir “On Writing” as follows: “I distrust plot for two reasons: first, because our lives are largely plotless, even when you add in all our reasonable precautions and careful planning; and second, because I believe plotting and the spontaneity of real creation aren’t compatible.” The ‘plot‘ mentioned in the quote would correspond to the ‘idea‘ in Denning’s column. As Denning said practices are the main source of innovations and ideas are afterthoughts to explain innovations that have already happened, King said stories pretty much make themselves in the course of writing and progress to theme. And King’s figurative expression for his creative process is really impressive: “stories are found things, like fossils in the ground“. Although I don’t know of many novelists, I imagine there are not a few novelists who take this type of approach. Haruki Murakami, who reportedly leads race for Nobel prize for literature as of writing this article (the winner turned out to be Mo Yan who happens to have the same family name as my wife), is one of them. This spontaneity would be essential for creative process and I think that human beings instinctively know it because, as King wrote, “stories are relics, part of an undiscovered preexisting world”

After discovering a concept, you need to put a label on it so that it can be a part of your knowledge. And through this label, you can view the world around you in a fresh-new viewpoint. This kind of concept-oriented knowledge building is the main focus of the Knowledge Creation in Piggydb.

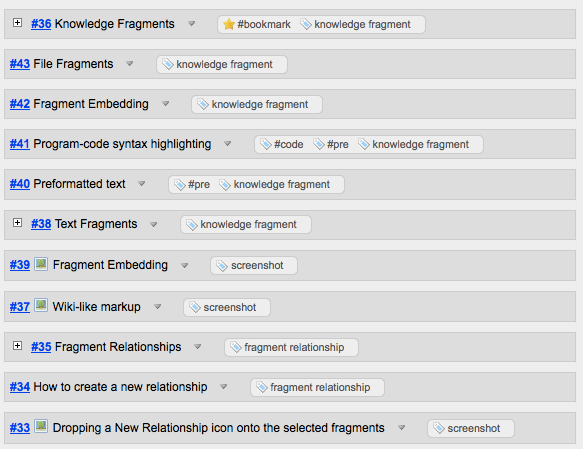

The most important feature of Piggydb in terms of concept-oriented knowledge building is Tag-Fragments. A tag-fragment, which is the kind of a knowledge fragment whose ‘as-a-tag’ attribute is enabled, can be used to represent a concept that you have discovered as in the above episode or selected as a theme in advance for your study or investigation. Originally, classic tags have played an assistant role in the Web 2.0 systems providing a lightweight way of organizing information. And, of course, you can use these tags to represent found concepts other than familiar categories. However, this means just grouping elements by concepts, which does not contain any structure for the concepts.

As you might know already, the labels of concepts themselves do not solely hold the value of your knowledge. They are just labels. The value resides in the context behind concepts, the context in which you have come to discover and build the concepts (the Internet is filled with fruitless communication triggered by responding to keywords without considering their contexts). Therefore, the important factor deciding the value of your concepts is how you structure this context information, and that’s why Piggydb introduces Tag-Fragment that supports two-layer structure allowing you to evolve found concepts into more rich and structured knowledge. While classic tags is no more than collective keywords for indexing, Piggydb’s tags can be treated as the same as the first-class information components (knowledge fragments) in a database, which means they can have their description and relationships to other components.

[To be continued]

The Piggydb Way: #1 Tag as Concept over Tag as Index

Posted: June 20, 2012 Filed under: essay, thepiggydbway 4 CommentsIn this series of articles ‘The Piggydb Way’, I will try to explain why Piggydb is so unique and useful in terms of knowledge creation compared to other information management systems and how it will change the way you organize information. I will do my best by squeezing my limited English skills to convey the whole notion of what Piggydb is all about. Your feedback is always welcome.

—-

I guess many of you regard or use Piggydb as an organizable notebook. But why do you organize your information in the first place? In most cases, its purpose would be to make it easy to find a piece of information you need later on.

There are countless applications and services that provide tools to do these things: folders, trees, tags, hyperlinks, etc. Compared to these applications, Piggydb has powerful tools: Fragment Relationships and Hierarchical Tags. But here in this series of articles, I’d like to explain that Piggydb aims not only to provide such tools for organizing information, but also to seek further value by providing a way to build your own ‘concept’ maps.

The most important feature of Piggydb is ‘tags’. However, you may not need them if you use Piggydb as an organizable notebook. Actually when I used it in the recent work to manage the project related information, I did not use tags at all except the system tags (#home, #bookmark, etc). Just connecting fragments was sufficient to manage the information (multi-parenting perfectly worked to organize the complex information). Heavy users may have realized that the roles of fragment relationships and tags are overlapped because both have similar functionalities in terms of ‘grouping’ fragments. So if you just need to organize information on your daily life or work, it would be sufficient to use only either of them.

Well then, why am I saying tags are especially important in Piggydb?

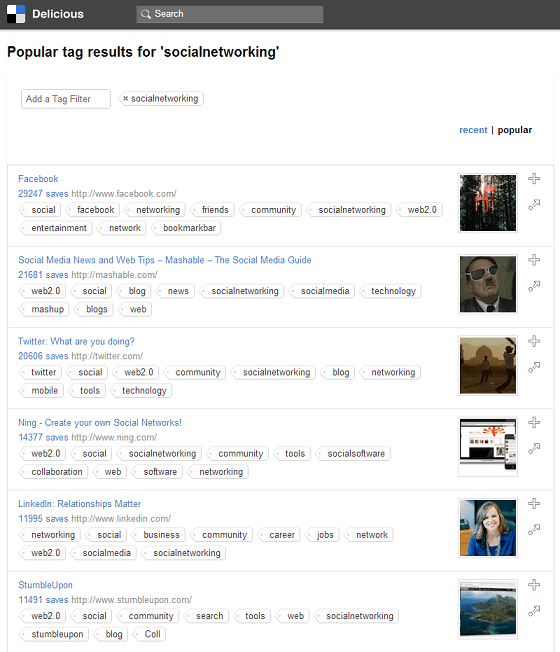

Tagging has become one of the primary ways people organize information since Web 2.0 services adopted it as their important features. Tagging was introduced as a more lightweight alternative to the existing classification systems such as hierarchies. Hierarchical classification systems manage categories by single-parenting tree structure and their vocabularies should be controlled carefully in order to work properly (controlled vocabulary). Although tagging was adopted as an effective alternative to hierarchies, there is a trade-off between these two systems. Tagging is certainly more flexible and easier to use in the way you can attach multiple labels you come up with to a piece of information while hierarchies force you to select a single category following the existing hierarchy. But what will happen when the amount and varieties of information increases?

Japanese economist Yukio Noguchi argued in his best-selling book published in early 1990s that any attempt to classify information to make it searchable is useless in the first place. He pointed out the problems in classification. One of them is the ‘Bat Problem’ which arises when classifying information and goods. Material things and information can have multiple attributes that are used respectively depending on the context (e.g. Bats have the properties of both birds and beasts). He also referred to Wittgenstein’s ‘Family Resemblance‘ principle, which states that “things which may be thought to be connected by one essential common feature may in fact be connected by a series of overlapping similarities, where no one feature is common to all (from Wikipedia)”. This idea also shows the limits of the traditional taxonomy (known now as ‘monothetic’).

The most difficult thing in classification is to maintain its consistency in the growth of the database. Not only will your database grow, but you yourself will also learn and then need to change your classification system. Noguchi explained this by introducing the ‘Theorem of the Ugly Duckling‘, which was proposed and proved mathematically by Japanese theoretical physicist Satoshi Watanabe. Here is the quote about this theorem from the book “Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition“:

From the formal point of view there exists no such thing as a class of similar objects in the world, insofar as all predicates (of the same dimension) have the same importance. Conversely, if we acknowledge the empirical existence of classes of similar objects, it means that we are attaching non-uniform importance to various predicates, and that this weighting has an extralogical origin. When we employ a concept, we usually understand that there is a group of objects corresponding to this concept that any two members of the group resemble each other more than a member and a nonmember. Two sparrows are very much alike, while a sparrow and a rose are not alike. It is natural to translate the term “to resemble” as “to share many predicates in common.” But this interpretation can be shown to lead to a denial of the existence of a class of similar objects by the following theorem, which I have dubbed the theorem of the ugly duckling. The reader will soon understand the reason for referring to the story of Hans Christian Anderson, because this theorem, combined with the foregoing interpretation, would lead to the conclusion that an ugly duckling and a swan are just as similar to each other as are two swans. (Watanabe 1969, 376)

Watanabe thought that any classification is arbitrary and inevitably biased by our cultural background.

With these problems in mind, you should realize that hierarchical classification turns to be only a representation of a limited perspective and how fragile it is for ever-changing knowledge management. Even tagging, which is more flexible and solves some of the problems such as the Bat Problem, cannot escape from the problem of maintaining consistency. Rather, in tagging where users can freely choose words, classification can more easily lead to the lack of control than hierarchies, for example, the resulting vocabulary will be filled with homonyms (the same tags used with different meanings) and synonyms (multiple tags for the same concept). To begin with, tagging has been popularized in the context of Folksonomy, in which searchability or comprehensiveness is not the major purpose of classification, but it aims at promoting communication among users triggered by matching tags for finding more valuable information efficiently.

I have explained how fruitless it would be to classify information for searchability so far, but it might not even need those stiff theories. You have probably experienced a situation where you had been organizing your classification with great effort, but you ended up not using most of it, and what you really needed was just a simple keyword search, haven’t you?

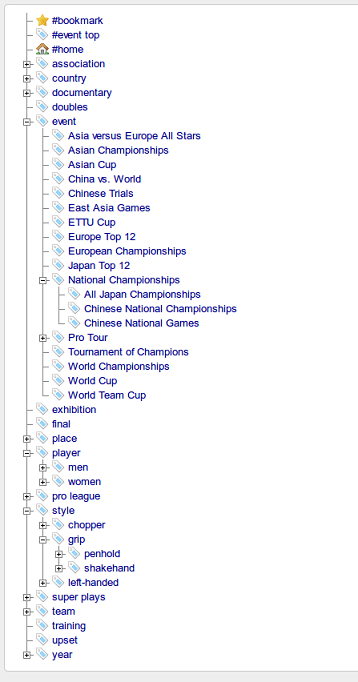

Still, I would be certain that there are many people who insist that it works, at least, for them, and actually there are such cases, which I call ‘Stable Classification Schema Case‘. The demo site Table Tennis Videos is a good example for this. But I won’t discuss this case further because it is not directly related to Knowledge Creation I want to focus on here.

So finally, after a long digression, I’m returning to the main point: why am I saying, in Piggydb, which does not have any features related to Folksonomy, the most important feature is tags?

The theorem of the ugly duckling proved that any classification is arbitrary, and this arbitrariness makes it difficult to maintain the consistency of classification, therefore, classification is quite limited as a way to build an index for information. However, if we change our point of view a little bit, on the other side of arbitrariness, couldn’t it be said that classification is creative in terms of expressing one’s thoughts, ideas, or lessons? As you know from tag clouds, your tags represent the essence of your database or lessons learned in the course of growing your database. In a traditional way of information management, the essence comes before building the content of a database, like defining a classification hierarchy as a container of information. What will happen if you reverse this process? You don’t create tags as a mere index for information, but as a reflection of your growing database and make them the central part of your knowledge.

I’m going to explain this reversal process more in depth in this series of articles, but before diving into it, in order to distinguish between these two tag usages, let’s call them respectively ‘Tag as Index‘, where tags are created for searchability, and ‘Tag as Concept‘, where tags are created to represent the important concepts learned in the growth of your database.

Next: The Piggydb Way: #2 Tags as First-Class Components

Tagging Turned Out to Be Not So Flexible

Posted: August 1, 2011 Filed under: essay 9 CommentsI’m about to start the development of V5.x after deciding that V4.23 is the final version of the V4.x branch except for bug fixes.

As I wrote before, as of V4.23, Piggydb has not achieved its most important goal yet. In the V5.x branch, I’m going to update the core model to aim at the goal I originally set. Some of the old features you depend on might be broken in these changes, so until the new features are fixed and stable, V5.x versions will be released as experimental.

Although there are many things to do in the plan of V5.x, I’d like to write a little about one of the most important things.

I think that the biggest design failure of the current Piggydb is “tagging”. I had a preconception that tagging would be unconditionally useful and flexible, and didn’t think much about it and actually I’d not been a heavy user of tagging. And I thought the problems of tagging would be solved with Hierarchical Tags.

Tagging, or classifying, works well if the whole system of classification won’t change much. For example, Table Tennis Videos is one of the Piggydb demo sites and it shows a good example of a tag hierarchy: country, player, date, event, play style, etc. These kind of hierarchies would be relatively stable as you could easily imagine.

I guess most of the users use Piggydb in more or less the same way. But this kind of usage, applying the known (ordinary) system of classification to your knowledge fragments, would not lead to the goal I originally intended. I want to focus on knowledge that will be changing in the course of a learning process.

The problem is that tags are mainly used to search information, as a mere index of content. If your system of classification has changed as time goes by, you have to modify the existing taggings according to the change. The maintenance cost will increase as the database grows and finally it would be out of control.

But still, I think the concept of tags is important for Piggydb.

Suppose Piggydb doesn’t have tags. You can structure your knowledge like Mind Maps, Outliners, or Wikis just by connecting knowledge fragments to each other. But, as the number of fragments increases, you will gradually lose the grasp of the whole picture of your knowledge. Tags would provide you with the overview of your knowledge in that situation. Yet you couldn’t rely on tags as a perfect index for your knowledge for the reason mentioned above.

With all these issues in mind, how should I change Piggydb?

Although I don’t have any decisive ideas, there are some that I think are important. One of them is to change the tag model so that a tag becomes a specific form of a knowledge fragment. As your knowledge base grows, at some point, you can turn a knowledge fragment which you feel is important into a tag as an important concept and it can be related to wider range of fragments to research it further.

An important theme of Piggydb is how it encourages users to create their own tag cloud based on their knowledge fragments, not on their known system of classification. This goal isn’t impossible to achieve with the current version if there are some instructions, but I believe that it is meaningless unless a software itself has an affordance to convey its philosophy to users.

Hierarchical Tags

Posted: May 2, 2011 Filed under: essay 8 CommentsLike many other Web 2.0 systems, Piggydb supports tagging to classify knowledge fragments.

While tagging is simply for classifying a piece of information and allowing it to be found again by browsing or searching, in the context of folksonomy, its simplicity (non-hierarchical keywords) enables organizing information by many people collaboratively, known as “collective intelligence”, and connecting like-minded people.

Piggydb is not a social networking application, so it concentrates on the classifying nature of tagging. In terms of classifying, tagging has many advantages over existing systems such as directories/folders and categories. Tagging is generally more flexible and less brain-racking, and is used to resolve the “Bat problem”.

The ‘Bat problem’ was coined by Japanese economist Yukio Noguchi to describe a problem which arises when classifying information and goods. Material things and information can have multiple attributes that are used descriptively depending on the context (Bats have the properties of both birds and beasts – http://mythfolklore.net/aesopica/milowinter/43.htm).

Bat problem: http://data.lullar.com/%E3%81%93%E3%81%86%E3%82%82%E3%82%8A%E5%95%8F%E9%A1%8C

However, tagging also has its own problems. One of them is losing the grasp of the entire set of tags when the number of tags is growing. Piggydb offers hierarchical tagging to tackle this problem.

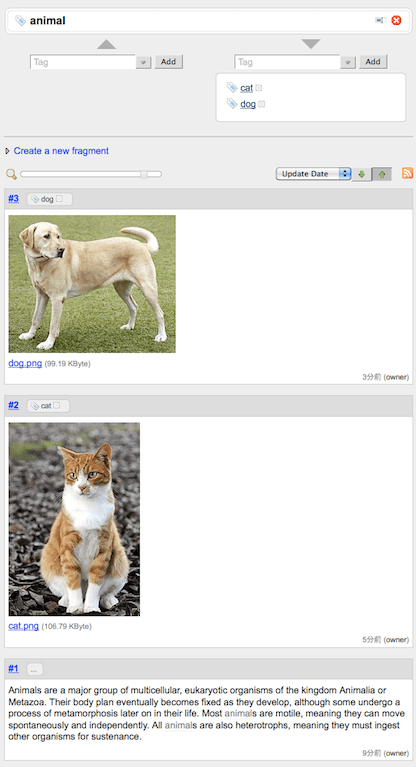

Hierarchical tagging allows you to classify a tag through other tags, exactly like knowledge fragments, and the classification is transitive; that is, if there is a tag “cat” classified with a tag “animal” and you classify some fragments with “cat”, then those fragment will be classified as an “animal” also. The hierarchical tagging feature allows you to classify fragments more naturally, and drill down a large number of fragments more easily and smoothly.

If you search fragments with the “animal” tag, all the fragments classified as “animal” will be selected, as shown:

Wiki, Mind maps, Concept maps and Piggydb

Posted: September 24, 2010 Filed under: essay 7 CommentsBefore I created Piggydb, I had been using a Wiki for storing and organizing my thoughts, ideas, article excerpts, and anything else I wanted to write down. Although a wiki provides an extremely simple and flexible way to organize your knowledge in a network structure, I came to feel that it was not well suited for what I wanted to do. As I used it more extensively, I found that the data structure of a wiki was not flexible enough when I want to reuse some part of a page in different context.

Another drawback of a wiki, for me, is that it encourages you to organize your knowledge in a top-down manner, that is, you have to select a main theme as a starting point. But I wanted to write down anything I thought could be useful and organize afterward, as needed.

So I decided to create a software program to meet my needs. The first concept was that users can input finer grained units of information (which I call “knowledge fragments”) and organize them more freely and flexibly. Also, since knowledge fragments can be classified using tags, I thought it would lead to a more powerful tool for knowledge management while retaining the simplicity of a wiki or other notebook applications.

But as I experimented with Piggydb’s knowledge creation, I found out that it did not work as well as expected. I thought originally some sort of structure would gradually emerge in the continuous organization of knowledge fragments with tags. But there’s something missing still in Piggydb to achieve this goal.

What is the missing part? I will try to illustrate this below by comparing two well-known knowledge representation techniques, “Mind Maps” and “Concept Maps”. Concept maps, which I happened to find about recently, are similar to the Piggydb concepts. The contrast between these techniques helps to understand the aim of Piggydb.

The principal difference between these techniques is the structure of their knowledge models. A mind map is a tree which has a central governing concept at its root, while a concept map is a network of concepts. Why is mind mapping far more popular than concept mapping? One of the reasons would be the simplicity of tree structure, which you can create quickly and afterward follow and comprehend easily. A mind map also helps you focus on a single topic during the organization of your knowledge. The combination of this strength of trees and visual images promotes human understanding dramatically, and it is why mind mapping is so popular as a tool to understand or memorize whatever you want to, in a short time.

On the other hand, concept maps are not as simple as mind maps and more difficult to create, but still easy to understand and intuitive to read. The strength of concept maps is their expressiveness which allows you to explain more complex relations (see the interesting example from the above site, it explains why we have seasons).

Piggydb adopts a network structure to represent knowledge as concept maps because a network is more capable of managing a large number of interrelated topics, so it is more suitable for a database-like system than a tree structure. Moreover, a network is more flexible and allows you to connect between concepts in different fields, which is called “cross-links” in concept mapping. That, in my view, is the key to creativity.

When I first saw concept maps, I thought that is where Piggydb’s knowledge creation process should lead. This process would start with collecting concrete materials, gradually evolve an abstract structure from them, and then, finally, produce a concept map-like conceptual knowledge map. But there is a part missing to realize this process, and as I wrote above, filling this gap will be the main theme of version 5.x.

One of the flaws of the current Piggydb is that when a user classifies fragments they tend to select categories they already know, which is the opposite of the aim of Piggydb: creating/finding new concepts. This is partly because the Piggydb’s tag system doesn’t much differ from the existing Web 2.0 tag systems and users tend to use it in a way they have already learned. In terms of the data models, tags should have been designed as a specific form of a fragment so that a user can create concepts from existing fragments and tags, and organize them in the same way.

You can use Piggydb as a wiki-like content management system or an Evernote-like database system, and I myself actually use it so in some cases, for example, Piggydb.jp. But as you already know, the goal of Piggydb is a little different from these systems. Although this goal is not fully achieved yet, I’m developing it to be a platform that encourages you to (re-)organize your knowledge continuously to discover new ideas or concepts, and, hopefully, to enrich your creativity.

Next: The Piggydb Way: #1 Tag as Concept over Tag as Index

Recent Comments